You’re not alone. Most people reach their deathbeds not having found them either.

That’s because they look in the wrong places, think inside tight boxes, or tackle the dilemma ass-backward. Many begin by making lists of their skills, aptitudes, and talents, then look for careers that match. Before anything else, they’ll check the pay rate and immediately stop exploring if not near their expectations. No surprise, then, that Gallup recently discovered 70% of Americans dislike their jobs.

For starters, I don’t know where we got the idea all jobs must be meaningful. I doubt Jesus found much meaning in carpentry, or Gandhi in law. And I know for a fact Buddha found his princely life utterly devoid of meaning. In all three cases, their life purpose found them. Either by way of an epiphany — like Jesus experienced when baptized in the Jordan River at age 30 — or when shuddering with indignation, like Buddha and Gandhi did when faced with injustice and human suffering.

Shallow are the souls who have forgotten how to shudder. — Leon Kass

On a train voyage to Pretoria, 24 year-old Mahatma Gandhi was thrown off a first-class railway compartment and beaten by a white stagecoach driver after refusing to give up his seat for a European passenger. That train journey was the turning point for young Gandhi who soon began developing and teaching the concept of “passive resistance” with the ultimate aim of freeing his homeland from the yoke of British colonialism. Thirty-seven years later, the Indian National Congress fulfilled Gandhi’s dream by declaring independence.

At 29, Siddhārtha shuddered when he fled from the ‘perfect’ world inside his royal palace, and, for the first time, witnessed the suffering of the common man in the street. Alleviating human suffering became his sole purpose. At 35, he reached enlightenment and became a Buddha.

It’s worth noting that all three exemplars — Jesus, Gandhi, and Buddha — died relatively poor, and that two of them were killed for their beliefs. It is also worth remembering that the word “passion” comes from the Latin pati— to suffer. As Nietzsche said, “if you have a ‘why’ to live, you can put up with almost any ‘how.’

What we get out of life is not determined by the good feelings, but by [the] bad feelings we’re willing and able to sustain to get us to those good feelings. What pain do you want in your life? What are you willing to struggle for? — Mark Manson

From Passion and Anger to Greater Purpose and Meaning

My passion is writing. Has been since the age of eight. I know it is, because when writing I experience flow, that mystical feeling where time stops. I also know it’s my passion because the longer I write, the more energized I feel. It has made me experience the vitality famous playwright William Herzog finds in his own work, and which he describes as follows: “A holiday is a necessity for someone whose work is an unchanged daily routine, but for me everything is constantly fresh and always new. I love what I do, and my life feels like one long vacation.”

While I don’t believe I was singled out at birth to be a writer, I absolutely love it, and that love makes me practice the craft with steely grit and unwavering discipline. Little by little, day by day, I am becoming better at it, though must confess there are times when it feels, not like a long vacation, but like torture. But as I tell boys in my latest book, there is beauty and nobility in hardship.

The road from intensity to greatness passes through sacrifice. — Rudolf Kassner.

And yet, all this time, my passion had served no other purpose than to cater to my own pleasure and delight. That is, until I shuddered, a little over a year ago.

For a long time, I had been angered by the endless string of mass shootings in the U.S. and had taken the time to research their true cause. I’d also been following the growing crisis in American boyhood and dimming prospects for men in general. But I did absolutely nothing about these issues other than getting increasingly angry and frustrated. Then, on New Year’s Day, 2019, I chanced upon this quote in one of my notebooks: “A man of genius is primarily a man of supreme usefulness” and it struck me with a shattering force.

I finally grasped what Greek philosopher Aristotle meant about vocation — that it lies at the intersection of one’s talents and the needs of the world.

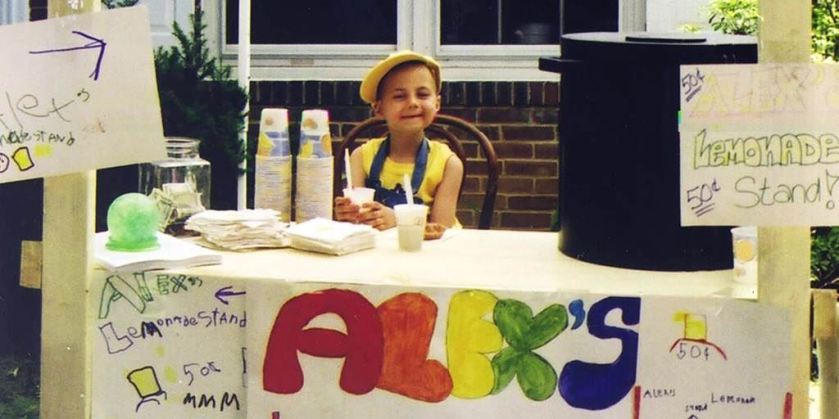

At last, at the ‘tender’ age of 57, I had found my purpose and decided to use my writing talent and passion to serve what I consider the most urgent need in today’s world: to initiate boys into becoming good men.

Thus far, I haven’t earned a dime from this work and hopefully never will, for as I tell boys in the book, one of the precepts of the Medieval Code of Knightly Chivalry is, “Focus on the good of your cause and not on its material rewards.” The word “knight,” I further explain, shares the same root with the word “hero,” meaning “servant.”

While my path opened through outrage, it is not the only way. Often, one’s purpose is found by way of an irrepressible enthusiasm for something one feels must be shared with the world. A crazy love! so to speak. The story of Vietnamese refugee David Tran and his giddy passion for his hot sauce Sriracha is a perfect example. His dream was “never to become a billionaire,” as Tran told Quartz when interviewed, “but to make enough fresh chili sauce so that everyone who wants it can have it. Nothing more.”

That “nothing more” has translated into a food empire now selling over $60 million dollars per year.

What if I don’t know what my passions are?

Here again, you’re not alone.

And it’s because most people shackle themselves to a narrow definition of who they are, what they think they’re good at, like, or may not like, so never move beyond their comfort zone. Hence the reason why so many could-be Jesuses remain in their wood shops, Gandhis in law offices, and Buddhas ensconced in their palaces, and the world doesn’t change nor heal.

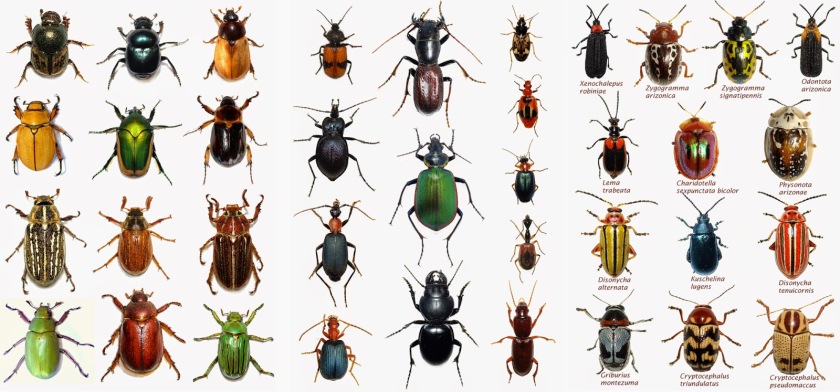

Who’s to say, for instance, that if you were to apprentice with a beekeeper you might not discover in yourself a natural talent for it, even a burning passion that will inspire you to run further with it and save honeybees from extinction and the world from starvation in the process? What a legacy that would be!

We’re not slaves, says Greek writer Nikos Kazantzakis in ‘Saviors of God.’ As soon as we are born, a new possibility is born in us. Whether we act upon it or not, we each bring a new rhythm, a new desire, and potential new promise to the Universe. But unless we are curious and courageous enough to go out and seek it, we won’t find it.

The two most important days in your life are the day you are born and the day you find out why. -Anonymous

In his practical and instructive guide, ‘How to Find Fulfilling Work,’ philosopher Alain de Botton says we should allow experience to be our mistress and let her take us “job dating” until we feel a spark. This process may include apprenticeships, internships, volunteering, or simply what he called “conversational research” where you spend an afternoon with a beekeeper, say, or a farmer, artist, chef, or a shamanic healer.

Vocation, Botton adds, is often something we grow into, not something we automatically find.

Before job dating, he recommends we let our imaginations run wild and think of 5 parallel universes where we’re allowed a whole-year-off to pursue any career we desire, then write down what it is about those five careers, or ways of life, that so moves and inspires us.

When I worked on this exercise, my deepest yearnings were for freedom, authenticity, serenity, and meaning.

Prodding deeper, I came up with this list:

- I want to quit the rat race… don’t want to be a moron, automaton, or commuter

- I don’t want to be enslaved by machines, bureaucracies, tedium

- I want to be whole, not a fragment of myself

- Do my own thing

- Live simply and frugally

- I want to deal with authentic people, not masks

- People matter to me, nature matters, beauty matters, wholeness matters

- I want to care for others. Give back. Pay forward. Heal.

At 54, I finally mustered the courage and broke free.

A man needs a little madness or else he never dares cut the rope and be free! — Nikos Kazantzakis

Another useful strategy recommended in Botton’s book is “The Personal Job Advertisement” in which we write down our talents, likes and dislikes, our yearnings, personal qualities and limitations, and the core values and causes in which we believe, and then send it to ten people who know us well asking them to recommend 2 or 3 career pathways that might fit. It then becomes a matter of experimenting with these possibilities in the real world.

A Means to an End

Not every job will be meaningful or engaging, as 70% of American workers have discovered. But it doesn’t mean the end of the world, nor that the promise that came with you when you were born will never see the light of day.

I freelance to pay my bills and hate every second while writing shit I could care less about. But I don’t complain. I see it as means to an end, affording me the freedom and time to bring my passion and talents to bear on what I do care about — the wellbeing and future of boys. If I can prevent but one mass shooting, I will die a happy man.

Your deep-seated frustrations with the world, your anger, outrage, or simply your irrepressible enthusiasms contain the clues to your purpose. Find that one need in the world that can be best served by your talents and you will have found your calling and unique path to a meaningful life. Just don’t expect a smooth ride, nor praise, fame, or rich rewards, and above all, don’t —please don’t wait until you’re 57. As poet Jimmy Santiago Baca said: “Life is not a rehearsal for living someday.”

Related reflections:

Warriors Wanted to Save the World!

Stop Sharpening your F*#king Pencil!

“Living your Truth” is only for Madmen