According to Roman myth, it had been foretold that one of the sons of Saturn would overthrow him, just as he had overthrown his father, Caelus. To prevent this, Saturn ate his children moments after each was born.

In every boy’s life there is a moment when he imagines his destiny outside the expectations of his parents. When that time comes, the deepest wound a boy can suffer is not receiving his father’s blessing.

My dad never overcame such devastating blow.

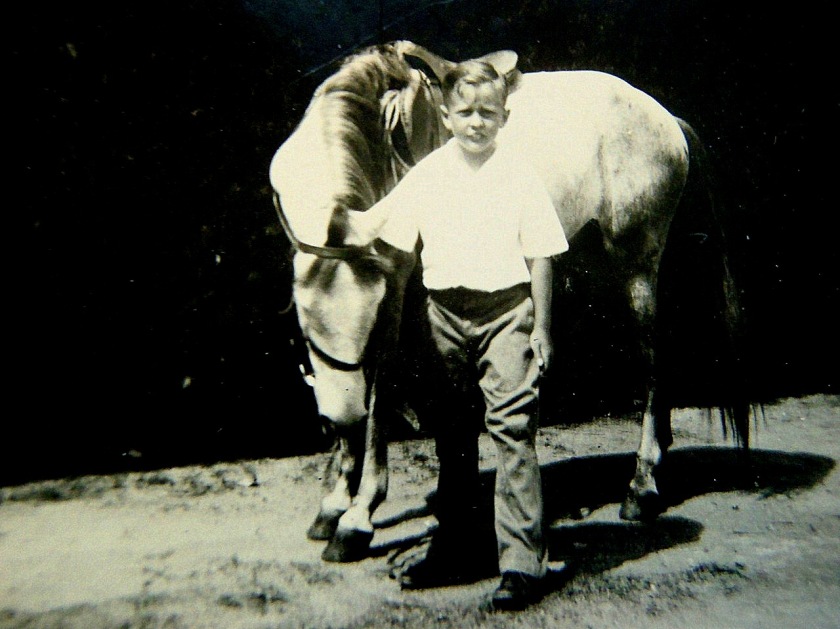

At age seven, right before World War II, he escaped Germany with his mother and moved to Guatemala to begin a new life at my grandparent’s estate, which, at the time, led out to grassy fields, steep ravines, streams, rivers, and roaring waterfalls. It was every boy’s fantasyland.

Precocious and inquisitive, Dad learned to read at age four and turned into a bookworm with an insatiable appetite for learning and discovery. He loved science fiction and the Tarzan of the Apes book series, devouring them all, more than once.

To ease Dad’s transition into his new environment, my grandfather bought him a horse and two dogs. Thereon, every afternoon after school, he’d set off on his mount to explore the vast wildlands of this fantastic realm. From a high point, he could see a shimmering blue lake, far in the distance, backdropped by four imposing volcanoes — two in permanent, fiery upheaval. His favorite resting spot was a waterfall plunging thirty feet into a crystalline pool teeming with crayfish he loved to catch. He’d stop there to swim and play with his dogs, always on the lookout for lianas by which to swing from tall tree to tall tree like Tarzan.

Guatemala was once ruled by the Maya, one of ancient history’s most advanced civilizations. The fields across which my father roamed were thus strewn with obsidian arrowheads, jade beads, stone axe heads, and pottery fragments which he collected and treasured all his life.

These wild experiences, and the books he read, filled my father’s young imagination with a stirring sense of adventure. By the time he was ten, he yearned to climb the highest mountains, trek across the most inhospitable jungles, and draw maps to guide other explorers. Swept-up in his excitement, he wrote about his dream, and, late one evening, waited for his father to return from work to share his budding aspiration.

I never liked my grandfather. He was cold and stern, stiff like a slab of petrified wood. It wasn’t until he died that Dad told me how the old man used to drag him down to a basement and kick a ball at him with such force it often bruised him. “Be a man! Toughen up! Don’t cry!” he’d yell at his son. My grandfather was also of the idea than a man’s identity is solely defined by his profession so worked long hours and was hardly present in my father’s life.

That night, taking Dad’s story from his hesitant, outstretched hands, the old man adjusted his wire-rim glasses and started reading. Dad, meanwhile, looked up at him with an eager sparkle in his blue eyes, waiting for his blessing.

Done reading, my grandfather looked down and scoffed:

“Tsk! So a nobody, that’s what you’re saying… a bum, basically. Is that all you aspire to?”

Before Dad could shake his head and explain, the old man’s callous fist crushed his dream and threw the crumpled paper on the floor. “You will write no more nonsense!” he thundered, and walked away.

In my mind, only two things can explain my grandfather’s reaction.

First, that he thought a man could only earn a living and provide for his family by holding a “respectable” job and feared climbing mountains and drawing maps would lead Dad to failure. In other words, he crushed my father’s dream out of love, wanting to protect him from hardship later in life.

Second, he was jealous, and wasn’t about to let his son bask in heroic limelight. As a boy, he too may have yearned to go on a wild adventure… on his own hero’s journey, but couldn’t, for whatever reason. Perhaps some other dream-crushing ogre stopped him in his tracks.

Whether A, B, or both, not receiving a father’s blessing is one of the deepest and most devastating wounds a child can suffer. Had his boyhood dream been honored, my father would’ve made a dashing world explorer. Instead, he became a businessman, just like his father, and lived to regret it.

As a father myself, I’ve always wanted the best for my two daughters and know how easy it is to buy into the prevailing cultural notions of success and wellbeing. Having also suffered great hardship in life, I found myself steering them in their early teens onto the college track out of a fearful wish to spare them from what I had suffered for not having gone to college myself. I now realize that while I was doing it out of love, my actions were misguided.

As we age, life has a very cruel way of robbing us from our youthful idealism and makes us stop asking the magical questions of childhood: ‘What if?’ ‘I wonder…’ ‘If only…’ One day, we simply stop building castles in the sky. We no longer believe the impossible possible and start playing it safe. So when our children come to us with their own dreamy castles, we call them “impractical” and crush them underfoot, just like my grandfather did.

If “security” and “safety” become watchwords by which [we] live, gradually the circle of [our] experience becomes small and claustrophobic. This suggests that to ask “Why face danger?” is the wrong question. The right question is “What happens if I try to build a life dedicated to avoiding all danger and all risk?” — Sam Keen, ‘Learning to Fly’

I wish Dad would’ve defied his father with the same courage displayed by Richard Halliburton, one of the world’s most dashing explorers and adventurers.

At age 18, Richard wrote this letter to his father in response to his wishes that his son return to his senses and back to Princeton:

Dad, you hit the wrong target when you write that you wish I were at Princeton living “in the even tenor of my way.” I hate that expression and as far as I am able I intend to avoid that condition. When impulse and spontaneity fail to make my “way” as uneven as possible, then I shall sit up nights inventing means of making life as conglomerate and vivid as possible. Those who live in the even tenor of their way simply exist until death ends their monotonous tranquility. No, there’s going to be no even tenor with me. The more uneven it is the happier I shall be. And when my time comes to die, I’ll be able to die happy, for I will have done and seen and heard and experienced all the joy, pain, thrills — every emotion that any human ever had — and I’ll be especially happy if I am spared a stupid, common death in bed. My way is to be ever changing, but always swift, acute, and leaping from peak to peak instead of following the rest of the herd, shackled in conventionalities.

Although he drowned at age 39 in a typhoon while sailing from Hong Kong to San Francisco, Richard had already lived a full and adventurous life most men would kill for.

During his short lifespan, he climbed the Matterhorn, got himself incarcerated at Devil’s Island, hung out with the French Foreign Legion, spent a night atop the Great Pyramid, rode an elephant through the Alps like Hannibal, played Robinson Crusoe on his own desert island, retraced the path of Odysseus, met pirates and headhunters, and bought a two-seater airplane he named the Flying Carpet and flew off to Timbuktu. He swam the Nile, the Panama Canal, the Grand Canal of Venice, and even the reflecting pool at the Taj Mahal. The chronicle of his adventures made him a bestselling author.

In contrast, my father became a businessman, an alcoholic, and for the last twenty years of his life merely a shadow of his former self. While he might’ve died younger than at 88, had his father blessed his boyhood dream, he would’ve lived on his own terms, fulfilling the destiny that was his to live and not the aspirations of someone else.

It is better to live your own destiny imperfectly, than to live the imitation of somebody else’s life perfectly. — The Bhagavad Gita

In ‘Men and the Water of Life,’ mythologist Michael Meade says, “If children were simply satisfied with what the parents offered them, they would remain children forever. It’s not simply that parents don’t try to give enough to the child; rather, it’s that whatever the parents give is never enough. The child has a destiny outside the imagination of the parents.”

If a father does not honor and bless the boy’s own destiny, the boy will grow to become another wounding father and devour his children, just like the Titan Saturn, in a never-ending cycle of wound upon wound.

Jeffrey Erkelens is the creator of ‘The Hero in You,’ a book for boys (10–13) meant to guide them toward an evolved expression of manhood and help them develop the character strengths needed to become caring and passionate men of noble purpose. Sign up here to receive updates on the book’s upcoming publication.